Baseball’s Golden Days in Hot Springs

May 3rd, 2013Where spring training got its start in preparing the boys of summer.

Baseball purists know this time of year means more than just transi- tioning from winter to spring. Spring training camps in sunny Florida and Arizona are now in full swing for all 30 Major League Baseball teams.

Baseball purists know this time of year means more than just transi- tioning from winter to spring. Spring training camps in sunny Florida and Arizona are now in full swing for all 30 Major League Baseball teams.

However, there was a time in its infancy, when big league teams came to a small mountain town in Arkansas known nationally for its healing thermal waters.

Yes, Hot Springs was the first collective destination spot for baseball spring train- ing. It may be hard to imagine it now, but from 1886 through the early 1940s, the Spa City attracted most of the game’s best teams and brightest stars.

“The real cornerstone of Hot Springs niche in baseball history was in 1886 when Hall of Famer Cap Anson was the manager and first baseman of the Chicago White Stockings and brought his team south to prepare for the season,” said Hot Springs native and resident Mike Dugan. Dugan is a member of the Society for American Baseball Research. He is the resi- dent expert on the city’s former connections to the national pastime. Sporting goods magnate A.G. Spalding owned the White Stockings (now known as the Chicago Cubs). He and Anson were working on a new way to get the team ready for the coming season. “Anson had learned about our mineral waters and spas and the reason he brought the team to Hot Springs was so they could, ‘boil out the alcoholic microbes’ in his hard- living players.”

The purpose was to get the players in shape by soaking in the spas, hiking the mountains and playing baseball in the more moderate climate. Spring training was born. In addition to Anson, the team included future Hall of Famers John Clarkson and Mike “King” Kelly. Another team member was Billy Sunday, who would later become a renowned evangelist. Stand today on the corner of Ouachita and Hawthorne streets in Hot Springs, look at the Garland County Courthouse and envision a baseball field once occupying the site.

The White Stockings practiced and played there that first year. A giant oak tree on the courthouse lawn dates back to that time. The White Stockings won the pennant that year, and more teams joined them in finding spots in the south to train for the season. “By 1915, all of the big league teams in baseball had trained in Hot Springs at some point,” Dugan said. Other teams that quickly followed the White Stockings to Hot Springs included the Pittsburgh Pirates, Cleveland Spiders and Cincinnati Reds, plus a host of minor league clubs. The Spiders featured, arguably, the great- est pitcher of all time, Cy Young. “Cy Young also played for the Red Sox and loved Hot Springs so much he returned regularly after he retired,” Dugan said. Young, baseball’s all-time winningest pitcher with 511 career victories, announced his retirement from the game in Hot Springs before the season started in 1911, changed his mind, then quit at the end of the sea- son. In 1938, the city celebrated Cy Young Day and honored him with a parade down- town. Chicago sold its field on Ouachita Ave. in 1896. Soon, other fields sprang up at the end of the trolley lines on Whittington Avenue.

The White Stockings practiced and played there that first year. A giant oak tree on the courthouse lawn dates back to that time. The White Stockings won the pennant that year, and more teams joined them in finding spots in the south to train for the season. “By 1915, all of the big league teams in baseball had trained in Hot Springs at some point,” Dugan said. Other teams that quickly followed the White Stockings to Hot Springs included the Pittsburgh Pirates, Cleveland Spiders and Cincinnati Reds, plus a host of minor league clubs. The Spiders featured, arguably, the great- est pitcher of all time, Cy Young. “Cy Young also played for the Red Sox and loved Hot Springs so much he returned regularly after he retired,” Dugan said. Young, baseball’s all-time winningest pitcher with 511 career victories, announced his retirement from the game in Hot Springs before the season started in 1911, changed his mind, then quit at the end of the sea- son. In 1938, the city celebrated Cy Young Day and honored him with a parade down- town. Chicago sold its field on Ouachita Ave. in 1896. Soon, other fields sprang up at the end of the trolley lines on Whittington Avenue.

Two teams that adopted Hot Springs as their spring home in the early 1900s were the Pirates and Boston Red Sox. The Pittsburgh Pirates and its Hall of Fame short- stop, Honus Wagner, started in 1901 and had 22 spring training visits through 1926. During that time, the Pirates played and lost the first World Series against the Boston Americans in 1903.

The Americans adopted the name Red Sox during the 1907 season. After two years (1907-08) of spring training in Little Rock, the Red Sox switched to Hot Springs. The Red Sox trained 13 springs there from 1909 through 1923. That led to the greatest baseball player of all time regularly coming to Hot Springs. The young, talented Red Sox southpaw quickly embraced the town and all of its blessings and vices like no one before or since. Nineteen-year-old George Herman Ruth was one year removed from St. Mary’s Industrial School for Orphans, Delinquent, Incorrigible, and Wayward Boys. It was 1915 when he arrived in Hot Springs with his Red Sox teammates for spring training. He was a promising pitcher.

Dugan has a copy of a 1915 photograph of Red Sox and Pirates players and fans pos- ing with Hot Springs citizen William G. Maurice. The Maurice Bathhouse gets its name from him. “It’s easy to see Honus Wagner — per- haps the greatest shortstop of all time — Bill Carrigan, Tris Speaker, another future Hall of Famer for the Red Sox,” Dugan said.

“Now, if you look carefully in the back row, you can make out the head of a young Babe Ruth.” Ruth fell in love with the city and all it had to offer. Golf and gambling were two of the passions he enjoyed with great gusto. He would be at the Hot Springs Country Club at 7:00 a.m. every day for 36 holes of golf before baseball practice. Ruth had no regard for money. The first year he came to Hot Springs he lost his entire big league salary before playing his first regular season game. He found the casi- nos and Oaklawn Park racetrack irresistible.

Early in his career, he was the best left- handed pitcher in baseball. He was a com- bined 47-25 during 1916-17 seasons. But Ruth was an even better hitter. He proved it with a long home run in a spring training game in 1918 against the Brooklyn Robins at Whittington Park. Ruth got to play first base that day. He responded with two home runs in two at bats, the second one a mammoth blast that landed across the street in the Arkansas Alligator Farm. The Red Sox traded Ruth to the New York Yankees in 1920. He continued visit- ing Hot Springs for a few weeks prior to joining the team’s spring training site. A big man, Ruth always seemed to be battling extra pounds packed on during the winter. He claimed the restoring waters at the bath houses helped him do that.

The Yankees began sending other veteran players to join him. But the undisciplined Ruth had a vora- cious appetite for food, alcohol and women. He partied continually and frequently left the spa city in worse shape than when he arrived. Finally, after missing the first half of the 1925 season due to poor health, the Yankees forbade him to return to Hot Springs. A habitual gambler, Ruth continued to frequent the city after his retirement fol- lowing the 1935 season. The story goes that in 1941, Ruth got involved in a high stakes poker game in Hot Springs that was rigged. He lost all of his money. The Bambino felt cheated and never returned.

The Alligator Farm across from Whittington Park, where the Babe launched that prodigious shot, is still in business. The Whittington Park baseball diamond is long gone, entombed beneath a parking lot at a Weyerhaeuser corporate office. Broken foundation slabs and long con- crete bleachers, large trees growing among them, are all that remains of the grandstand once tucked into the side of a mountain. If you know what you’re looking for, there’s evidence of a field of dreams where Hall of Famers once played.

The first mention of Whittington Park was in 1894. In 1895, the St. Louis Browns came to use the field, but quickly retreated to Little Rock due to a smallpox outbreak in Hot Springs. By 1909, the Sox, Pirates and Brooklyn all trained regularly in Hot Springs, creating a need for another baseball field. The Red Sox usually stayed at the Majestic Hotel. The team built another ballpark at the other end of the trolley line, where the Boys and Girls Club now sits. They named it Majestic Field. The Red Sox, Reds and Brooklyn all trained there. A year later the Detroit Tigers, Cleveland Indians and Washington Senators of the newly created American League came to the spa city and trained at Whittington Park. In 1912, Brooklyn, along with the Philadelphia Phillies, built a new ball field on ground behind the Alligator Farm, across the street from Whittington Park.

It became Fogel Field, named for Horace Fogel, owner of the Phillies. The baseball diamond is gone, but the field is still there. Other big league teams that later trained in Hot Springs included the St. Louis Cardinals and Philadelphia Athletics. Unlike players today who sign auto- graphs at the ballpark but seldom mingle publicly with fans, the early stars often lounged in hotel lobbies or walked along Central Avenue and bathhouse row posing for photos with fans. “They were accessible to the public,” said Steve Arrison, chief executive officer of the Hot Springs Advertising and Promotion Commission. “Though some, like Ruth, were larger than life, they enjoyed their celebrity status and didn’t shy away from their fans.” Arrison says it was a historic time in the city’s past when movie stars, entertain- ers and celebrities regularly visited Hot Springs. According to Dugan, Arrison and other historians of that period, the national pastime ruled the city from late February through March.

It became Fogel Field, named for Horace Fogel, owner of the Phillies. The baseball diamond is gone, but the field is still there. Other big league teams that later trained in Hot Springs included the St. Louis Cardinals and Philadelphia Athletics. Unlike players today who sign auto- graphs at the ballpark but seldom mingle publicly with fans, the early stars often lounged in hotel lobbies or walked along Central Avenue and bathhouse row posing for photos with fans. “They were accessible to the public,” said Steve Arrison, chief executive officer of the Hot Springs Advertising and Promotion Commission. “Though some, like Ruth, were larger than life, they enjoyed their celebrity status and didn’t shy away from their fans.” Arrison says it was a historic time in the city’s past when movie stars, entertain- ers and celebrities regularly visited Hot Springs. According to Dugan, Arrison and other historians of that period, the national pastime ruled the city from late February through March.

The Baseball Hall of Fame has a little more than 200 player members. More than half of them trained in Hot Springs at some time during their careers. They include such greats as Satchel Paige, Walter “Big Train” Johnson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, “Lefty” Grove, Carl Hubbell, Johnny Evers, Al Simmons, Casey Stengel and Rogers Hornsby, just to name a few. “The players liked coming to Hot Springs so much that in 1932, Ray Doan devised a plan to open a baseball school at the park on Whittington,” Dugan said. The month-long school opened Feb. 15, 1933. During the school’s tenure, instruc- tors included Arkansas native sons Dizzy and Paul Dean, “Schoolboy” Rowe and Lon Warneke, as well as Hack Wilson, George Earnshaw, George Sisler, Johnny Evers, Al Simmons, Grover Cleveland Alexander and Cy Young, among others. Rogers Hornsby eventually bought the school from Doan and relocated it to Majestic Park, where it operated until 1952. “My dad, Pat Dugan, grew up across the street from the field on Whittington,” Dugan said, “He told the story of how he used to mow the grass at the school and got to meet many of the legendary players of that era. “He told me one of the neatest things that happened was when Jimmie Foxx of the Philadelphia Athletics and later with the Red Sox, who was his favorite player, would play catch with him in the mornings. The future Hall of Famer gave my dad a first baseman’s mitt which he kept for years.” The Pirates’ Wagner was another base- ball great who fell in love with the city and invested in its youngsters.

Wagner owned a sporting goods store in Pittsburgh. In 1909, he read in the local paper that Hot Springs High School was trying to form a basketball team. Wagner had a traveling team of baseball players who played basketball during the off- season to stay in shape. He and some of his Pirate teammates volunteered to teach the boys at Hot Springs High how to play basketball. Wagner had uniforms and shoes shipped from his store in Pittsburgh for the team to wear. One of the members of that first Hot Springs High School team was Leo P.

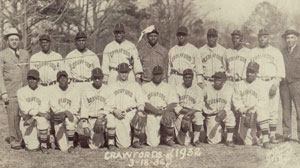

McLaughlin, who was the city’s mayor dur- ing the “mob era” of the 1930s and ‘40s. Though its weather was better than the bitter cold and snow to the north where most teams were located, Hot Springs was often rainy and not ideal for training. Following the 1926 season, most major league teams had relocated further south to places like Florida. The golden days of Major League Baseball teams having spring training in Hot Springs was finished. While entire teams didn’t return, numerous players already familiar with Hot Springs continued to train there on their way south before their team’s spring training offi- cially opened. Minor league teams and some Negro League teams began filling the void left by big league team departures.

As individual careers ended and World War II began, the last of the major leaguers were gone after 1942. In its place, minor league baseball began flourishing in Hot Springs. Now future stars were get- ting their start there. The Hot Springs Bathers of the old Cotton States League played at Whittington Park. Later, the team had its own facility, Bathers Park, next to the old Majestic Field (later renamed Dean Field and Jaycee Park). The Bathers kept organized baseball going in Hot Springs from 1938-41, until the outbreak of World War II. Many play- ers went to fight in the war, and play didn’t resume until 1947. The Bathers’ last season was 1955. To commemorate and maintain the his- tory of the time when baseball thrived for six weeks each year in Hot Springs, Dugan and other fans formed a committee within the Society for American Baseball Research known as the “Deadball Era” (1900-1920). Meeting every other year in March, some 25-50 members travel to the spa city dur- ing the same time the old teams once con- verged on the city for spring training. They give presentations and visit the old parks, reliving the “golden days,” as Dugan refers to them, when baseball brought the world to Hot Springs.