Reaching for the Brass Ring: A Portrait of Doan’s 1937 Baseball School

Monday, January 13th, 2014by Mark Blaeuer

The following is an attempt, based on available sources, to provide a context for the memories of Col. Albert Wiest, whose article follows mine in this volume. In his article Col. Wiest writes about attending the Ray L. Doan All-Star Baseball School in Hot Springs in 1937.

Hot Springs was still a baseball town. True, its heyday was past—those halcyon Februaries and Marches when three or four major league clubs would show up for spring training each year, the total number of players swollen by a plethora of individual athletes who believed the place so healthful, they trekked here on their own. By the 1930s, teams were sending fragmentary rosters instead, especially batteries and “fat men” who needed to shed avoirdupois in Arkansas’s renowned thermal baths. This dwindling pattern would hold through the 1950s

Hot Springs was still a baseball town. True, its heyday was past—those halcyon Februaries and Marches when three or four major league clubs would show up for spring training each year, the total number of players swollen by a plethora of individual athletes who believed the place so healthful, they trekked here on their own. By the 1930s, teams were sending fragmentary rosters instead, especially batteries and “fat men” who needed to shed avoirdupois in Arkansas’s renowned thermal baths. This dwindling pattern would hold through the 1950s

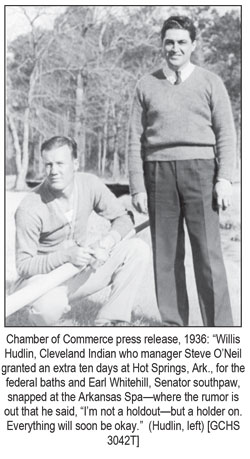

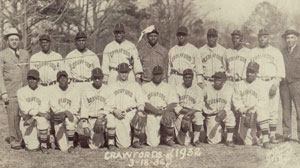

with occasional exceptions, mostly Negro league squads (able to boast their own future Hall of Famers) contributing to the overall baseball legacy of Hot Springs. Several major leaguers, like Al Simmons and Mel Harder and Earl Whitehill and Willis Hudlin, continued to swear by the resort, wintering here. One player, Lon Warneke, grew up in the area and kept a permanent residence nearby.

Into this milieu strode Ray L. Doan. Doan was born in Iowa in 1896, and he would die there in 1969. In the first half of the twentieth century, his name was synonymous with the phrase “sports promoter” (and among those who were not fans of his, the word “huckster”). His clients included Olympian and pro golfer Babe Didrikson, the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro leagues, and miscellaneous House of David teams known for mixing their version of the national pastime with beards and a fun-to-watch activity called pepper. He was the self-proclaimed “father of donkey baseball.” According to author Timothy Gay, Doan said, “I’m also the fellow who thought up playing softball with the infielders and outfielders tied to goats.”

At one time or another, many of the aforementioned clients were guests in the Spa City, but Doan’s work meant the most to raw hopefuls who made the pilgrimage to his “All-Star Baseball School.” Adolescent males came here from practically every U.S. state and several Canadian provinces, the majority of boys no doubt imagining stardom. The stars in their eyes had names, too: Doan recruited a slew of major leaguers to serve as instructors at his school. Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander, Clyde “Deerfoot” Milan, Urban “Red” Faber, and many more taught here over the six years of its Hot Springs incarnation.

The school operated in Hot Springs between 1933 and 1938. In 1939 Doan shifted the enterprise to Jackson, Mississippi, where enrollment flagged. In 1940 and 1941, winding down, the Doan school was lodged at Palatka, Florida. He also tried setting up a traveling baseball school for the summer of 1940, but it seems not to have caught fire. By then, a veritable thicket of schools for budding rookies had sprung up, so Doan’s educational institution was hardly unique. There was, in fact, another such nursery in Arkansas in 1937, in Little Rock under Bobby Harper, who caught for numerous minor league aggregations during the 1920s and 1930s. (In 1938 yet another baseball school would arise, in El Dorado under Frank “Blackie” O’Rourke, an infielder for six major league clubs over fourteen seasons.)

In addition, in this era major league clubs commonly held mass tryouts, hundreds of potential players venturing onto the “apple yards” to vie for spots in a given team’s organization. The shotgun strategy was less cruel than it sounds, as professional baseball could not yet rely on the dynamo of intercollegiate athletics to generate prospects. Some minor league teams would stuff their rosters with green youngsters from these open-to-anybody combines or from baseball factories like Doan’s. St. Louis executive Branch Rickey’s farm system was beginning to sink roots in 1932: “Furthermore, as a feeder to all these teams, is the Cardinal baseball school at Springfield, Mo., where 300 rookies of rawest ray serene are vaccinated with elemental baseball serum . . . In charge of this baseball cradle are 11 former major league players.”

There were precursors. The great player and manager Buck Ewing had a related notion in 1901 in Cincinnati with his correspondence course on baseball. The Miami Herald broached the concept of a real school in 1913. Charles Kelchner, a major league scout disappointed in the quality of minor league play, started a school in 1919. In 1921 Boston Braves manager Fred Mitchell endorsed and predicted the idea’s expansion. A 1907 Boston Doves catcher, Jess Orndorff, appears to have been the first to “go large,” with his 1928 National Baseball School in Los Angeles. Over a number of years, he employed several erstwhile major leaguers for sages.

Doan souped up Orndorff’s jitney model and revved its engine, hiring active stars as well as old- timers: “. . . association with these major league players in Hot Springs takes a lot of the inferiority complex out of the youngsters.” Doan shrewdly planted his kindergarten in the U.S. midsection, accessible to all, but chose a town that reveled in publicity: “Passing through Hot Springs with the Davids one time, he suddenly hit upon the idea of a baseball school.” Doan’s establishment soon dominated, operating in concert with The Sporting News, a St. Louis-based but nationally circulated “Bible of Baseball” (more about this relationship, anon; Orndorff had also found this to be a perfect venue in which to advertise).

From 1935 through 1940, initially affiliated with Doan, National League arbiter George Barr taught an umpiring school in Hot Springs. In 1937 he had thirty students. These included William Glass and Walter Jones, both of Hot Springs, and football celebrity Forrest “Frosty” Peters (age thirty-two, just seven years younger than Barr). By 1931 Peters had been an offensive back with Montana State, the University of Illinois, and four NFL clubs; in one 1924 game he drop-kicked an amazing seventeen field goals.

Barr’s program, according to his prospectus for 1938 (dated 1937) was made up of the following:

Opening week—while players are lectured and limbered up—three daily sessions are the order of business at the UMPIRE SCHOOL, morning, afternoon, and evening. During the first week, a few motion pictures, dealing with baseball subjects are shown, but the time is chiefly devoted to lectures . . . Since good umpiring is largely dependent upon good physical condition, each day-time lecture ends with a hike up one of the two Ozark peaks that flank the city . . . Through field-drills, the proper position for each play-situation is educated into the men. The Baseball School devotes several days to batting drill and these workouts are

UMPIRE SCHOOL, morning, afternoon, and evening. During the first week, a few motion pictures, dealing with baseball subjects are shown, but the time is chiefly devoted to lectures . . . Since good umpiring is largely dependent upon good physical condition, each day-time lecture ends with a hike up one of the two Ozark peaks that flank the city . . . Through field-drills, the proper position for each play-situation is educated into the men. The Baseball School devotes several days to batting drill and these workouts are

utilized by our umpires. One is placed in each batting cage and familiarized with the positions and stances for working back of the plate . . . By this time, a regular schedule of games is instituted and lecture periods are cut to one per day, since mornings and afternoons must be devoted to umpiring games on the field. In the night lectures, Mr. Barr brings a complete resume of the day’s activity, progress, and mistakes before the group.

Tuition was $50. The 1937 umpire school ran from February 15 through April 1. When Doan left, Barr worked with the Hornsby school. About half of Barr’s protégés, on average, landed umpiring jobs, but he would not refer his graduates automatically. Therefore, leagues wishing to hire from his reservoir of candidates trusted him.

Barr, like Doan, eventually found the grass more emerald-tinted in sunshine-happy Florida, moving his flock to Orlando in ’41. There, he operated in conjunction with the Joe Stripp Big League School of Baseball. In 1938 Stripp introduced the novelty of a tall mirror beside home plate as an aid to improving a student’s batting stance.

Preferring to stick with Hot Springs after Doan left, Rogers Hornsby steered his own baseball “college” here from 1939 through 1941 (he taught the school in Fort Worth in 1942), from 1948 through 1951, and again from 1955 through 1956.

Doan attempted to resurrect his old school at Hot Springs in 1961 and even pondered integrating the student body and the faculty (he intended to bring in John “Buck” O’Neil, then a scout for the Chicago Cubs but formerly a longtime player and manager with the Kansas City Monarchs). Doan corresponded with city officials and advertised in several issues of the Sporting News that the school would open on March 1. A squib in the March 8 issue of the News indicated the opening would be postponed until June 1. I found no further mention of the school, anywhere, and have concluded that Doan’s effort went for naught.

The promoter faced an American society that was evolving on numerous fronts. The same Sporting News page announcing his school’s delay in opening also carried ads for four baseball “camps” designed not only for teens but also for kids down to eight years old or younger (the Ken Boyer camp, at Montauk, Missouri, had no age limits whatsoever). These camps could charge rates exceeding $100. The primary motive for holding these camps during summer was that parents would not have to choose between baseball and formal education for their children. If parents were involved with a boy’s desire to attend Doan’s 1937 school, it might often have been to hope that six weeks in Arkansas would “get baseball out of his system” and nudge him toward the alternative: traditional work. Nor would the immediate goal of Baby Boom

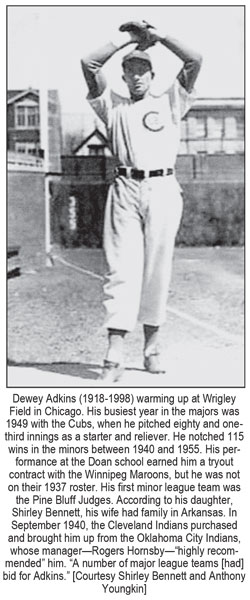

Dewey Adkins (1918-1998) warming up at Wrigley Field in Chicago. His busiest year in the majors was 1949 with the Cubs, when he pitched eighty and one- third innings as a starter and reliever. He notched 115 wins in the minors between 1940 and 1955. His per- formance at the Doan school earned him a tryout contract with the Winnipeg Maroons, but he was not on their 1937 roster. His first minor league team was the Pine Bluff Judges.  According to his daughter, Shirley Bennett, his wife had family in Arkansas. In September 1940, the Cleveland Indians purchased and brought him up from the Oklahoma City Indians, whose manager—Rogers Hornsby—“highly recom- mended” him. “A number of major league teams [had] bid for Adkins.” [Courtesy Shirley Bennett and Anthony Youngkin] participants have been to enter the pro scene. Baseball was a more diverse proposition by the affluent 1960s, with increased opportunity across multiple age brackets: Little League, high school programs, etc. Hence, Doan decided to push his school’s starting date back, but in so doing, he would have run smack into the already well-developed world of baseball camps.

According to his daughter, Shirley Bennett, his wife had family in Arkansas. In September 1940, the Cleveland Indians purchased and brought him up from the Oklahoma City Indians, whose manager—Rogers Hornsby—“highly recom- mended” him. “A number of major league teams [had] bid for Adkins.” [Courtesy Shirley Bennett and Anthony Youngkin] participants have been to enter the pro scene. Baseball was a more diverse proposition by the affluent 1960s, with increased opportunity across multiple age brackets: Little League, high school programs, etc. Hence, Doan decided to push his school’s starting date back, but in so doing, he would have run smack into the already well-developed world of baseball camps.

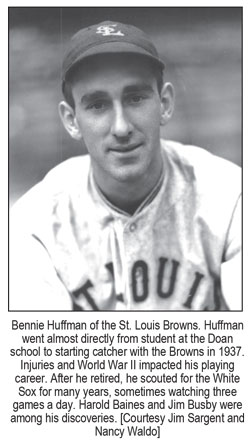

Not that Doan had smooth sailing before. Some journalists and baseball grandees in the 1930s looked askance at baseball schools, implying it was unethical—if not larcenous—to pocket fees from callow youth of suspect aptitude. The Yankees owner, Col. Jacob Ruppert, was among the critics: “I see no reason for the schools, and I am astonished that they are tolerated.” Doan, to his credit, never claimed that the school’s graduates would achieve fame and fortune: a wise precaution, as the ex-pupils rarely drew sports page ink of a major league variety. One ad for the school trumpeted that eighteen alumni had “won berths” on major league teams. Thus far, I have confirmed that seven students, including two of Wiest’s fellow novices in 1937, appeared in The Show as regular-season performers (Harry Chozen with the Cincinnati Reds; George Dickey with the Boston Red Sox and Chicago White Sox; Dewey Adkins, Doan class of ‘37, with the Cleveland Indians, Washington Senators, and Chicago Cubs; Sam W. Narron with the St. Louis Cardinals—later a bullpen catcher and coach with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates; Ben Huffman, Doan class of ‘37, with the St. Louis Browns; Thurman “Joe E.” Tucker with the White Sox and Indians; Johnny Grodzicki with the Cardinals). Beyond those who attained major league status as players, one alumnus donned an American League umpire’s suit (Bill McKinley) and one rose to executive echelons (Vaughan “Bing” Devine, Cardinals general manager and New York Mets president). In addition, Douglas “Scotty” Robb, who attended Barr’s 1936

school, umpired in both the National and American Leagues; the umpire school was still considered part of Doan’s operation at that time.

Undeniably, Doan lined up minor league tryouts for skilled students, and many enjoyed careers in the bush. Earning the coin of the realm while pursuing a dream, rugged and transitory though such diamond labors often proved, was nothing to scoff at during the Great Depression. The rest of his charges likely cut a finer figure on their local sandlots and town circuits. Doan pointed out

that his “for profit” school instructed students for a full six weeks, as opposed to club-sponsored free camps, which cut the less gifted kids loose after a day or two. Apparently, though, a student was not obligated to stay for the whole six weeks; Wiest mentioned that he was present for three.

When Albert Wiest and his buddy hitchhiked and freight- hopped from North Dakota to “Bathburg,” they  encountered a vast assemblage of boys like themselves here, all of them eager to learn the arts of batting, fielding, and base-running at the feet of major league masters. The staff that year consisted of the forty-year-old Doan (a semipro pitcher whose arm went bad, he had coached at Springfield College, Massachusetts, and been an athletic director in the Army), three main instructors, and “a score of others.”

encountered a vast assemblage of boys like themselves here, all of them eager to learn the arts of batting, fielding, and base-running at the feet of major league masters. The staff that year consisted of the forty-year-old Doan (a semipro pitcher whose arm went bad, he had coached at Springfield College, Massachusetts, and been an athletic director in the Army), three main instructors, and “a score of others.”

Assorted Luminaries at the 1937 Doan School

Rogers “Rajah” Hornsby: This forty-year-old hitting legend (then manager of the St. Louis Browns and beginning his last year as a player) was arguably “head man” among the instructors. He taught batting, of course, but also offered tips in glove technique to his embryo infielders. By March 7, Hornsby was in San Antonio for the Browns’ training camp.

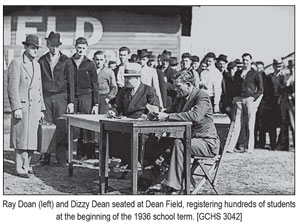

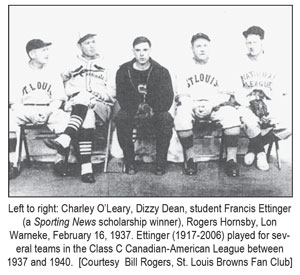

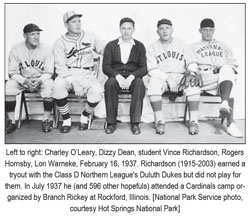

Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean: The “loquacious moundsman” from Lucas, Arkansas, was a faculty veteran at age twenty-six, and reporters visiting the school frequently sought snippets about his demand for a $50,000 salary from Cards management in 1937. His final day that term was February 18.

Lon “The Arkansas Hummingbird”/“Country” Warneke: The former Chicago Cub hurler, age twenty-seven, was now Dean’s teammate with St. Louis after an October trade. A January 15 blurb in the Sentinel-Record announced his signing to the Doan staff: “Warneke can walk from his home to the baseball campus to hold class. He recently moved here from his Norman, Ark., farm.” By March 2, Warneke was at the Cards’ camp in Daytona Beach.

Charley O’ Leary: At age sixty-one, this Detroit Tiger of yesteryear (and ex-vaudevillian) was less than three years removed from having stroked a pinch hit and scored a run with the Browns. By 1937 he was Hornsby’s sidekick—as coach with the Browns, as a trusted partner in teaching basic glovemanship to Doan’s neophyte infielders, and, during the first week of the session, in helping the youngsters apprehend their batting lessons. He arrived in San Antonio for the Browns’ training camp no later than March 11.

Hank Severeid: A journeyman backstop, he thumped his mitt for roughly a decade with the Browns, but his stalwart presence aided two pennant-winning clubs in the twilight of his major league career—the Senators in 1925 and the Yankees in 1926. By 1937, at age forty-five, he was a player-manager in the minors. Fresh off a stint with the Omaha Robin Hoods, he had already Hancocked a deal to pilot the Galveston Buccaneers (this would be his final summer as a player). He arrived at Hot Springs on February 16 to share the tricks of his craft with Doan’s apprentice catchers; these ought to have included Wiest. By March 16, Severeid was in Galveston for the Bucs’ opening workout.

Johnny Mostil: In his prime a fleet outfielder with the White Sox, Mostil twice nabbed an American League title for stolen bases. Now, at age forty, he was skipper of the Eau Claire Bears, in the Cubbies chain, and still an able fly-chaser. Under his reins, the Bears had taken the

1936 Northern League crown. He mentored Doan outfielders: per one article, “the ‘faculty’ includes a recognized

expert at every position on the diamond.” Naturally, students would have felt lucky to absorb his bag-purloining methodology.

expert at every position on the diamond.” Naturally, students would have felt lucky to absorb his bag-purloining methodology.

Joe “Germany” Schultz: Stationed largely at infield slots upon arrival in the bigs, he logged substantial outfieldtime as his career meandered. He spent more years with the Cardinals than with any other club. Later, he managed in the minors. Having reached age forty-three, Schultz was, in 1937, a high-caliber scout in the Cards’ farm system. By early March, he was reportedly judging horsehide talent in Riverside, California, and later that month, in Houston. While at Hot Springs, regardless of any scouting he might have done, he assisted Mostil with outfielders.

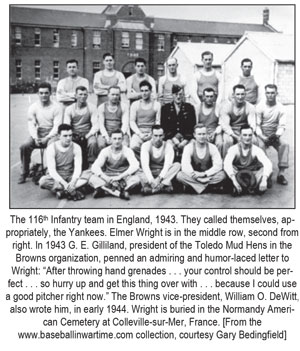

Walter “Union Man” Holke: In his salad days Holke was a first baseman, primarily for the Giants, Braves, and Phillies, and the forty -four-year-old still could wear multiple caps. Aside from managing the Terre Haute Tots in the Class B Illinois-Indiana -Iowa (or “Three-I”) League, he doubled as scout for their parent club, the St. Louis Browns. Labeled an actual instructor in Doan brochures, he stayed at theschool for at least two weeks, appearing with colleague Jack Ryan sometime before March 15. Holke was admittedly searching out prospects he could spirit away for his Hoosier outfit, and he did go north with several players from the school. One of these young men, pitcher Elmere P. “Elmer” Wright, went on to whiff 212 batters over the course of his season, 90 with the Tots and 122 for the Mayfield (Kentucky) Clothiers of the Class D Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee (or “Kitty”) League. His National Guard unit was mobilized the fall before he would have attended the Browns’ spring training (the Browns were keeping close tabs on his progress in the minors). Overseas, in southeast England, during the two weeks leading up to D-Day, Wright

was still tossing a baseball. Former college catcher Hal Baumgarten (later a consultant during the filming of Saving Private Ryan) said, “Wright was fast. I had to put a double sponge in the glove.” Elmer Wright was killed at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944.

was still tossing a baseball. Former college catcher Hal Baumgarten (later a consultant during the filming of Saving Private Ryan) said, “Wright was fast. I had to put a double sponge in the glove.” Elmer Wright was killed at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944.

Lew Fonseca: A former major league player and manager, “sweet-singing baritone,” and film enthusiast, thirty-eight-year old Fonseca crisscrossed the country as “super salesman of the American League.” Several late 1936/early 1937 articles listed him as an instructor at the Doan school in 1937. Also, a Wilbert “Wib” Henkel, in a 1999 syndicated column on collectibles, asserted that he had been a Doan student in 1937 and possessed a Fonseca autograph. Between February and June that year, Fonseca was on a six-thousand-mile tour throughout the eastern U.S. with 1910s and 1920s junior circuit shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh. The pair could easily have swung west and shown their popular movie, Heads-Up Baseball, at the school. If so, they might not have lingered at the bathing capital. Fonseca: “We have a solid schedule for one-day stands at colleges, CCC camps, luncheon groups and father-and-son groups.” Umpire George Moriarty directed the “six-reel talkie,” which was “sponsored by the Fisher Body Division of General Motors.” The movie had a cast of “more than 50 American leaguers.”

George “Gorgeous George”/“Gentleman George” Sisler: The retired Browns first- sacker had been one of the original nestors at Doan’s 1933 school. By 1937 he was boosting softball for the masses and running a sporting goods store in St. Louis. Sisler was forty-three when the session began and less than two years away from getting his own passport to Cooperstown.

George “Gorgeous George”/“Gentleman George” Sisler: The retired Browns first- sacker had been one of the original nestors at Doan’s 1933 school. By 1937 he was boosting softball for the masses and running a sporting goods store in St. Louis. Sisler was forty-three when the session began and less than two years away from getting his own passport to Cooperstown.

Wid “Spark Plug” Matthews: This forty-year -old “official in the expansive Cardinal farm system” had a short playing career with the Athletics and Senators in the 1920s. He later worked for the Dodgers, Cubs, Braves, Mets, and Angels. His greatest achievement may have been signing Ernie Banks for the Cubs.

Bob “Bullet Bob”/“Rapid Robert”/“The Heater from Van Meter” Feller: As far back as December, when Doan originally convinced the young hurler to participate, Tribe management tried to squelch his involvement, understandably fearing he might ruin his phenomenal arm. As late as February 25, he was mulling his opportunity “to coach a few days at the Doan Baseball school.” Ultimately, Feller’s role was reduced to that of “prize exhibit” for a single day. Doan said of the eighteen-year-old sensation, “I wanted to get a typical American boy” to inspire the students.

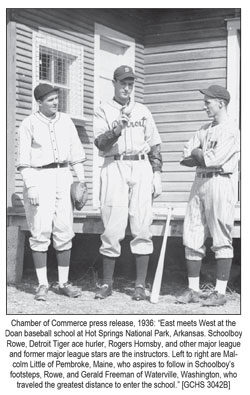

Lynwood “Schoolboy” Rowe: The Detroit pitcher suffered an accident en route to Hot Springs on February 15. “His automobile collided with the rear end of an oil truck” near Prescott, but his scratches, cuts, and broken nose were quickly “patched up” at a hospital there. On the sixteenth he informed reporters at the Majestic Hotel that “there’s nothing the matter with the old wing, thank goodness! My car was badly damaged and I finished the trip by bus to Arkadelphia, remaining there overnight and coming here this morning.” His former high school coach in El Dorado, Bill Walton, chauffeured him from Arkadelphia. One news story indicated the twenty- seven-year-old slab-man was only in Hot Springs to soak in the baths prior to traveling on to the Tigers’ training camp at Lakeland, Florida. Another had it that Rowe announced he would assist at the Doan school until March 1. Players in town for their own training purposes did lend a hand at the school if they happened by, and Rowe had been on the staff in 1936.

Miles “Spike” Hunter: This Hot Springs native was thirty-five when the session began. With the Little Rock Travelers in 1936, then with the House of David, he would serve as player- manager of the 1937 Jonesboro Giants in the Class D Northeast Arkansas League. In 1938 he plied his trade in a similar capacity with the Hot Springs Bathers. The Sporting News of April 8 labeled him a Doan instructor. The March 27 New Era concentrated on Hunter’s quest for young material with which he could stock his team.

Wilmer “Rip” Schroeder: The twenty-eight-year-old minor league twirler (his career lasted from 1930 through 1940) was hired as “boys’ supervisor” for 1937. Schroeder’s duties were to “arrange housing accommodations, ascertain the religion of each boy and see to it that he answers the roll call at that place, and in general supervise after-hours conduct.” Schroeder may have been one of those “Three Competent Counsellors” lukewarmly touted in a February 18, 1937, Sporting News ad aimed at potential late registrants for the course. Post-baseball, he was destined to be the sheriff of Scott County, Minnesota, an “internationally known” pigeon breeder, and a dedicated Red Cross volunteer.

Homer Cole: Defending the safety of his school, Doan wrote, “We employ two college graduate trainers to take care of sprains and muscular soreness.” Half of that duo was the twenty -nine-year-old University of Illinois grad Cole, who in 1936 worked with the North Carolina State football program under Heartley “Hunk” Anderson. In the 1940s Cole was “on the training staff of the [Chicago] Bears.” During World War II, Navy Lieutenant Cole was gridiron boss at Arkansas A&M (due to its V-12 training school) and took his Boll Weevils to the 1944 Oil Bowl.

Homer Wright: Overseeing the students’ “general health” was “Dr. Wright, one of Hot Springs’ most prominent physicians and surgeons.” Wright turned thirty-seven a few days after the school opened. He was an athlete himself, competing in tennis tournaments across the South. Wright was apparently not the only doctor associated with the school this year. A March 10 Dallas Morning News editorial quoted Doan: “We have a clinic of seven doctors who are at our students’ service day or night . . .” Thermal baths were also available as needed.

Jack Ryan: This venerable Cardinals scout, along with Browns scout Walter Holke, witnessed the 1937 session’s waning days. Now sixty-eight, the quondam major league catcher (as well as coach and manager at lower levels) had settled into the vocation of identifying players who had promise, then funneling said youngsters into the professional ranks.

Pat Monahan: Rumored to have been a pitcher in his youth, the forty-eight-year-old ivory hunter was exploring Doan’s jungle by February 20 on the Browns’ behalf. This formidable raconteur seldom lacked for confidence or garrulity, dishing out his “endless fund of information about players” and “thousands of stories.” In a radio stunt, he once extemporized for twenty-two straight hours.

Individuals Named Only Once as 1937 Doan School Instructors

The December 25, 1936 Omaha World Herald listed Dodgers manager Burleigh Grimes and the immortal Tris Speaker as teachers for the upcoming term at Doan’s school. (Speaker was voted into the Hall of Fame the next month; Grimes, “the last legal spitballer,” would have to wait until 1964 for his own induction at Cooperstown.) Also noted was Dutch Zwilling, then manager of the Kansas City Blues, who were minor league grangers on Yankee acreage. I found no other source linking any of the trio to Hot Springs during the appropriate time frame, not even later issues of the same paper. All three were 1936 faculty members, and the Nebraska scribe might simply have assumed they would return.

From Start to Finish, 1937

The school, for boys age fifteen and up (that year the top age was twenty-five), ran from February 15 through April 1 or so, but much occurred prior to mid-February.

The January 9 issue of the New Era reported: “The thermometer took a nose dive in Hot Springs yesterday, but the first harbinger of spring arrived, nevertheless. With a cold wave riding on his heels, Ray Doan . . . blew into town to make arrangements for the 1937 term . . .” A nineteen- year-old from Massachusetts was the early bird among the students, showing up in Hot Springs two days behind Doan.

From his desk at school “headquarters” in the Como Hotel, Doan took care of business. He replied promptly to copious inquiries about whether disastrous Midwestern flooding had spread to Garland County: “Hot Springs is high and dry, never has been threatened, and is a couple of hundred miles away from such danger.” One of his toughest duties was to turn down applications from boys who were still in school, as the Baseball School’s vernal semester conflicted with standard pedagogic calendars. Sometimes he had to do this in person if a boy suddenly quit his classes and popped up here. Doan likely disseminated last-minute information about expenses, too. Tuition was $40 for March, according to circulars (cost for the first two weeks was unspecified; a 1936 ad listed the full fee as $60, exactly as Wiest recalled, but $50 if paid before January 20). Room and board was “obtainable in clean, respectable hotels and private homes for $7 a week or less.”

On January 27, Doan addressed the regular meeting of the Hot Springs Kiwanis, providing an optimistic forecast about his upcoming school.

Early the next month, Doan formally divulged the names of eleven of his 1937 professors. On February 4, the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat enumerated the mavens: Dean, Warneke, Hornsby, Feller, Sisler, Severeid, Mostil, Fonseca, Schultz, Holke, and Matthews. In March, a “ranting” letter from Doan to the Dallas Morning News posited: “Such men… aren’t hired for a song.” He slipped one other detail into his missive: “During the course of the school we use 100 dozen baseballs.” These “three typewritten pages of testimony” were sent to combat a negative editorial penned by George White, a skeptic of baseball schools. Doan was “reported to have cleared in the neighborhood of $100,000” from his educational work, so he wanted to remind everyone that he had expenses.

On the sixth, Doan released intelligence of a bold scheme: “Several days ago Mr. Doan wired President Roosevelt, requesting that he deliver a message to the boys when they assemble for their first meeting [February 15]. Since that time a lengthy telegram also has been sent Senator Joe T. Robinson, [who] was asked to assist in getting the president to speak over long distance telephone to the Doan baseball pupils. The Southwestern Bell Telephone company, it was announced, is ready to install equipment that will amplify the president’s voice, so that every one in the room will be able to hear it.” Neither FDR’s daily appointment logs nor Eleanor Roosevelt’s daily newspaper columns nor any other subsequent accounts offer so much as a hint that the gambit was effective.

The February 14 Sentinel-Record stated that Doan had met “during the past week” with “a group of representative Hot Springs community leaders” about “a program of activities for the leisure time of his students.” Doan wanted the boys to experience “one evening’s entertainment” per week, so they could get to know local citizens and, later, speak well of the Spa City in their hometowns. “S.A. Kemp, chamber of commerce president, called the meeting to order and explained its purpose . . . Elmer

The February 14 Sentinel-Record stated that Doan had met “during the past week” with “a group of representative Hot Springs community leaders” about “a program of activities for the leisure time of his students.” Doan wanted the boys to experience “one evening’s entertainment” per week, so they could get to know local citizens and, later, speak well of the Spa City in their hometowns. “S.A. Kemp, chamber of commerce president, called the meeting to order and explained its purpose . . . Elmer

Crowley, Garland county recreation leader; Miss Carrie Lou Ritchie, YWCA executive; and Floyd Huddleston, Boy Scout executive, were among the group to offer many interesting suggestions.”

In the weeks preceding February 15, an election had been underway. The Sporting News would soon award ten scholarships to prodigies craving instruction at Hot Springs. Readers could cast their ballots for candidates (all write-in) by enriching the publication. A year subscription counted as 400 votes for the stripling of choice, six months got him 175, and three months garnered 75. A cheaper option allowed backers to clip a “Scholarship Coupon” from the News and mail it in, each coupon worth 5 votes.

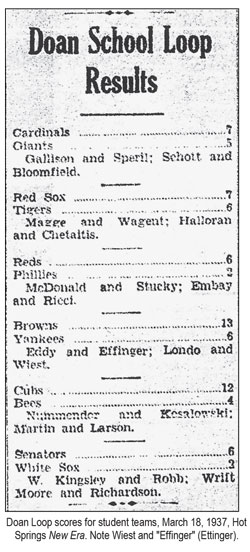

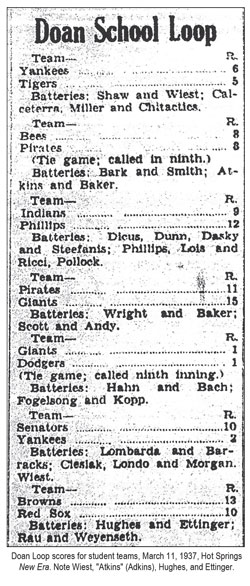

The Sporting News announced these ten winners, in descending order of votes received: Albert Wild, Collinsville, Illinois; William Enos, Cohasset, Massachusetts; Edward Osick, Jr., St. Charles, Missouri; Arnie Velcheck, Thorp, Wisconsin; Arthur C. Eddy, National City, California; Warren Kellogg, Lansing, Michigan; Harold Koopmann, Plymouth, Wisconsin; Edward Hughes, Richmond, Virginia; Joseph Rappazini, Negaunee, Michigan; and Francis Ettinger, Sebago Lake, Maine. All were to receive “free tuition, room and meals and $20 travel allowance” and be “equipped with uniforms made by the Rawlings Mfg. Company, St. Louis, Mo. and with ‘Lefty O’Doul’ shoes made by the Brooks Shoe Mfg. Company, Philadelphia, Pa.” Wild racked up a whopping 19,900 points. The February 25 issue also put Al Pepper of Washington, D.C. in the select group; the previous week’s results had him finishing fourteenth. The March 18 issue ran a picture of the suited-up winners in Hot Springs, and a twelfth young man, Joe Contini of Dover, Ohio, had been added. His vote total put him in twelfth place, per the original announcement. In the photo, “The Sporting News,” in Old English font, adorned the spotless Rawlings jerseys.

At 9:00 a.m., February 15, an “informal opening” of the school began at the “school headquarters, Ouachita avenue and Market street.” Unless Doan had use of another building in that vicinity, it was apparently the Como Hotel again. There, S. A. Kemp welcomed students to Hot Springs. This location may have been where Wiest registered and proffered his I.O.U. (acceptance of young Albert’s token belies criticism that Doan was completely mercenary) and where at least a few indoor chalk talks would have been held “in the event of inclement weather conditions.”

At 9:00 a.m., February 15, an “informal opening” of the school began at the “school headquarters, Ouachita avenue and Market street.” Unless Doan had use of another building in that vicinity, it was apparently the Como Hotel again. There, S. A. Kemp welcomed students to Hot Springs. This location may have been where Wiest registered and proffered his I.O.U. (acceptance of young Albert’s token belies criticism that Doan was completely mercenary) and where at least a few indoor chalk talks would have been held “in the event of inclement weather conditions.”

Local sportswriter Roy Bosson reported that 373 students had “journeyed to Hot Springs, Ark., by Pullman, bus, truck, freight and the thumb route to attend” the school: “One group from Wisconsin rolled in on a dilapidated truck, while two from New York arrived in style, driving a Packard.” Latecomers were still showing up. The tally would have been higher, in Doan’s opinion, except for cancellations caused by fear of flooding.

Bosson continued: “In greeting the students, Doan stressed the fact that his school is conducted on a ‘frank basis.’ ‘If, at the end of the school, a student has shown no natural ability we tell him to go home and forget baseball, other than as a recreation.’”

The school used three playing fields: Ban Johnson at Whittington Park (current site of Weyerhauser offices and parking), Older (above the Alligator Farm), and Dean “at the end of Morrison avenue” (where the Boys and Girls Club grounds are today). At that time, Dean Field had two diamonds. “On rainy days, when the students are unable to get outdoors,” the aspiring lads received instruction indoors. “By diagrams, actual word and motion pictures the instructors point out the fundamentals . . .” Rain or shine, teachers conducted classes at night, “skull features” with “a large blackboard.”

As no rain fell on February 15, everybody betook themselves to their assigned pea patches.

Two men from the Chicago Daily News accompanied Doan and Hornsby on the jaunt to Whittington Park. At Ban Johnson Field, Hornsby put seventy-nine student infielders “through their paces.” The youngsters “were sent trotting twice around the park and then given brief instructions. They were told to ‘hold your steam’ for a few days and not to throw away their arms. The Rajah made them stand at the plate one by one, showed the proper stance and gave them such pointers as only one of his experience can.”

The gruff Hornsby apparently excelled with boys: “When [the students] ‘take a lap’ around the field, he jogs along beside them, kidding and scuffling with them. Before the first day of class was over, most of them were calling him ‘Rajah.’” (He was less popular with major leaguers of his acquaintance, many of whom found him ill-tempered, unpredictable, and blunt; Hall of Fame shortstop Travis Jackson, of Waldo, Arkansas, once uttered, diplomatically: “He had a good way of making everybody irritated.”)

From Doan’s office, Warneke and Dean “jumped in Warneke’s car and headed for Dean Field, where nearly 100 ambitious young pitchers and catchers were awaiting them.” The ratio was about two-thirds hurlers to one-third backstops. “Dean lined up the pitchers and catchers and started warming them up.” According to one article, this meant calisthenics. “‘And don’t let me see any of you boys bearing down,’ yelled the Diz. ‘You’ll have plenty of time to limber up your arms and legs.’ Dean sent the pitchers in squads of four to Warneke, who, standing in the box, would have the boy show him how he pitched. Then, in most cases, Lon would show the boy a better way.”

Warneke was encouraging. To “one chap who wore glasses,” he effused, “Holy mackerel! Look at that kid pitch! Son, I am going to put you up against Diz for a strikeout record.” To another student: “Young fellow, you’ve got the stuff that makes pitchers. I mean it, too. There’ll come a day when you will step into the box and feel that you’ve got everything, that the opposing team is at your mercy. Your fast one will zip over and your curves will cut the corners, and you will split the heart of the plate. When the day comes there will be a little fellow standing back of the plate and he will break your heart. Every time you throw over a strike what will that little fellow say, Diz?”

Dean chimed in on cue, “He’ll yell ‘Ball’ . . . You see, that fellow is blind.”

Dean chimed in on cue, “He’ll yell ‘Ball’ . . . You see, that fellow is blind.”

A third man, silent until now, spoke up: “Will you two guys do me a favor?”

Dean: “Yes, Mister.”

“Remember those nasty cracks you just made and repeat them when the season is on and I’m calling ‘em. Will you do that, please?”

“Well, if it isn’t our old pal, George Barr,” Warneke said loudly, and Barr “joined in the big laugh that followed.”

The Dizzy One could also be pragmatic: “Dean studied the style of each young pitcher, advised him of ways to strengthen his delivery and then showed them how he pitched.” A bit of moralizing came in the bargain: “The main thing’s control. And to have control you’ve got to have control of yourself—live clean, let booze alone and don’t smoke to excess.”

As for the youngling outfielders, one article claimed they worked out at Dean Field under O’Leary. Another indicated they were among the group Hornsby led at Ban Johnson. Either scenario might suggest that Doan’s two outfield specialists, Mostil and Schultz, had not yet arrived in Hot Springs.

For the entire aggregation, “a hike over the mountains was in prospect for [the] afternoon.”

That night, the school’s formal opening and banquet took place at the Eastman Hotel dining room, where “elaborate preparations” had been made. A thirty-minute program, slated for eight o’clock, included speeches by Doan, Hornsby, Dean, Warneke, O’Leary, Barr, Peters, and Mayor Leo McLaughlin. The remarks were broadcast over Hot Springs radio station KTHS. Dean imparted this nugget to pupils: “When you get to be a big star, some tight baseball managers and owners will try to cut you down on your salary. Don’t let ’em do it. Do like I’m doing right now. Stick for everything you are worth.”

On February 16, photos were taken. The previous afternoon, Doan had queried his students, “How many of you would like to have your pictures taken sitting in a group chatting with Dean, Warneke, and Hornsby? All of you who would, hold up your hands.” Allen Tilden’s “Every Now’n Then” column in the February 16 Arkansas Democrat reported that “every hand in the classroom went up.” The images produced that day—at least the three I have examined—were deficient in the “chatting” aspect, but, as Tilden wrote, “It’s real work for Dean, Warneke, and Hornsby. Imagine yourself posing for approximately 300 pictures in a single day.” Nonetheless, many of the school’s alumni would have treasured these souvenirs.

Ben Epstein of the Arkansas Gazette visited the school on February 20. “Rain forced the young buckos indoors today for the second straight day but it failed to dampen their enthusiasm. Professor Doan hired the Hot Springs High School gymnasium, divided up time for the teams and they went at it on the asphalt ‘diamond.’” The practice leagues noted by Wiest had come into existence.

Ben Epstein of the Arkansas Gazette visited the school on February 20. “Rain forced the young buckos indoors today for the second straight day but it failed to dampen their enthusiasm. Professor Doan hired the Hot Springs High School gymnasium, divided up time for the teams and they went at it on the asphalt ‘diamond.’” The practice leagues noted by Wiest had come into existence.

Wiest’s memoir also describes a lecture by “some guy on the stage, armed with a bat,” in “an old union hall.” One wonders who he saw, and where. On the twentieth, at the high school gym, “Professor Hornsby was in charge of the morning session. In a way, the Rajah was handicapped. He hit a measly .424 in [1924] and over .300 for goodness knows how many seasons, which well qualifies him to the art of assaulting that apple. However, the bad weather put him on the spot of sermonizing on how to field and throw a ball.”

Among would-be hurlers Epstein encountered were H. T. Weaver of Mt. Ida and Norman Scott of Marianna, both in the Warneke clan: Scott a first cousin, Weaver a nephew. “‘Uncle Lon might have the pitching edge but you just get us in a tobacco-spittin’ contest,’ snapped H.T., who is a dead ringer for the former Cub and present Cardinal moundmaster.” Weaver pitched in the Cardinal organization for eight seasons between 1939 and 1949. Scott pitched in the Tiger farm system for seven seasons between 1941 and 1951.

Warneke clan: Scott a first cousin, Weaver a nephew. “‘Uncle Lon might have the pitching edge but you just get us in a tobacco-spittin’ contest,’ snapped H.T.,

Epstein interviewed another “carefree youth” on the twentieth: “Mr. Doan said student James Vinson of Junction, Ill., is the school’s problem child and it is likely he will injure some one if

he isn’t curbed. He throws with either hand and bats from either side. Two kids now are nursing head-hickeys because James lobbed one over left-handed and then crossed ‘em up with a righthanded peg. ‘I don’t mean any harm,’ says the six-foot farm boy . . . ‘I was born left- handed. After about 10 years of left-handing, my folks decided left-handed folks aren’t up to snuff and they urged me to try eating, chunking and batting from the right side. Well, I kept that up for six years and now—I’m pretty pert with either hand. It’s loads of fun. Hornsby can’t do it.’”

Flame-flinger Bob Feller paused at Hot Springs on February 27, in the company of Indians coach (and watchdog, probably) Wally Schang. They had rail tickets for New Orleans, the Indians’ training site. While at the school, Feller proudly discussed his newly acquired command of the curve. Having met their one-day obligation, the two again boarded the train. Earl Whitehill, presumably in tip- top condition after an extended stay at the Vapor Valley, joined them. All three rode to Memphis to rendezvous with the main Tribe contingent, on its way down from Cleveland.

Flame-flinger Bob Feller paused at Hot Springs on February 27, in the company of Indians coach (and watchdog, probably) Wally Schang. They had rail tickets for New Orleans, the Indians’ training site. While at the school, Feller proudly discussed his newly acquired command of the curve. Having met their one-day obligation, the two again boarded the train. Earl Whitehill, presumably in tip- top condition after an extended stay at the Vapor Valley, joined them. All three rode to Memphis to rendezvous with the main Tribe contingent, on its way down from Cleveland.

Much of the tutoring was said to be incorporated into live games. Despite the loss of marquee instructors by mid- March (partly explaining Wiest’s comments about their scarcity), the school had enough boys to set up sixteen teams in two leagues. The rationale was that this permitted “students a chance to develop and show what they can do under fire.” The 1937 Doan teams, following major league precedent, were called the Athletics, the Bees (the Boston National League franchise commenced a five-year stretch as the Bees in January 1936, but changed back to the Braves while the 1941 season was in its infancy), the Browns, the Cardinals, the Cubs, the Dodgers, the Giants, the Indians, the Phillies, the Pirates, the Reds, the Red Sox, the Senators, the Tigers, the White Sox, and the Yankees (for whom evidence of Wiest’s toil is found beneath the Hot Springs New Era subhead “Doan School Loop Results”). “For four weeks starting March 1,” Doan wrote to the Dallas Morning News, “we play a schedule of twenty-two games in which all students participate.”

By session’s end, about one-third of the fledgling ballplayers had been tendered professional contracts.

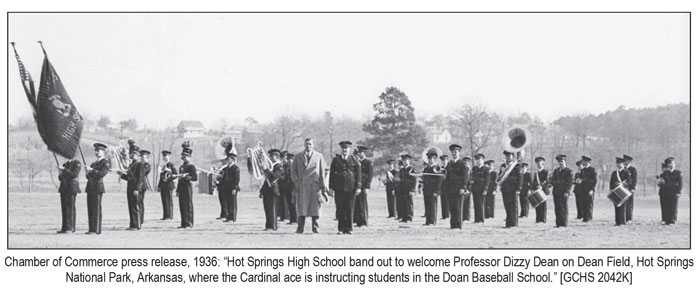

Although George Barr’s pupils gained experience by umpiring the curricular tilts, Barr himself “officiated” at least twice, in a climactic March 21 doubleheader at Ban Johnson Field. “General John J. Pershing, here for a brief rest, has been extended an invitation to throw the first ball in the second [game] which starts at 3 o’clock, while the Hot Springs High school band has also been invited to attend and play during the ceremonies. The first baseball game will begin at 1 o’clock.” In the first game, the “Ray Doan All-Stars” whipped a Greenwood, Arkansas, nine by the tune of 8-5. The nightcap saw contract recipients of the “National League” frustrate their “A.L.” counterparts, 7-5. In another feature that afternoon, “the field day exercises, carried on in conjunction with the twin bill, found Keith Powell, Lansing, Mich., winning the base circling honors with his good time of 14.5 seconds. Charlie Burnett, Kilgore, Tex., won the baseball throwing contest for catchers.”

The Sporting News revealed that Miles Hunter had just become manager of the Jonesboro club. He took eleven students with him to northeast Arkansas: “The youngsters are Bill Menser, Lefty Hughes, Wess Ray and Bill Rumfelt, pitchers; Andy Bach, catcher; Wily Sunderland, outfielder, and Klein Powell, Joe Cantini, Benny Labello, Roland Hamilton, and Al Pepper, infielders.” Jonesboro, along with Abbeville, Louisiana, of the Evangeline League, “recruited entire teams from the school.” Judging by data compiled at Baseball-Reference.com, only two of Hunter’s picks made the Jonesboro team. Of those, only Edward Hughes played more than one year in organized ball. His seven-season/nine-team/eight-league odyssey began at Jonesboro in 1937 and ended with a single inning pitched for the 1946 Dunn-Erwin (North Carolina) Twins in the Class D Tobacco State League.

The school closed for the year on March 27. On the twenty-ninth, Doan climbed into a car and departed for Muscatine, Iowa. With him were his wife and son, who had been in Hot Springs for six weeks. Before motoring off, Doan pronounced his 1937 term “more successful than any of the previous sessions,” but warned: “If we can obtain more playing fields we will have a much larger school next year, but unless the present situation is remedied the next school will not be a large one.” He “also expressed a desire for better housing for his students next year.”

His 1938 session would attract a record 450 students. After 1938 the Ray Doan school bell would ring no more in Hot Springs. The Doan baseball school had, for a few years, been as close as most Doan youngsters would get to a brass ring—a fabulous career in the big leagues.

Acknowledgments

A special tip of the cap to Steve Arrison, Nigel Ayres, Gary Bedingfield, Shirley Bennett, Tom Hill, Andreas Raht, Liz Robbins, Bill Rogers, the Allan Roth Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research, Jim Sargent, Thor Stratton, Nancy Waldo, and Anthony Youngkin.

Sources

Advertisements and correspondence in Doan School and Barr School files, Garland County Historical Society.

Arkansas Democrat, various issues, 1937.

Arkansas Gazette, various issues, 1937.

Baseball-Reference.com, accessed at www.baseball-reference.com.

Baton Rouge Advocate, various issues, 1937-38; 1943-45.

Baton Rouge State Times, various issues 1935; 1937-38; 1968.

Bedingfield, Gary. Scotty Robb, accessed at www.baseballinwartime.com.

Bedingfield, Gary. The Bedford Ballplayers, accessed at www.baseballinwartime.com.

Bennett, Shirley, Telephone interview. June 26, 2013.

Bowling Green Daily News, July 1, 1999.

Cleveland Plain Dealer, various issues, 1936-37, 1940.

Columbus Daily Enquirer, July 26, 1919.

Dallas Morning News, various issues, 1937-38.

Decatur Herald-Review, January 23, 2011.

Devine, Bing with Tom Wheatley. The Memoirs of Bing Devine: Stealing Lou Brock and Other Winning Moves by a Master GM. New York City, New York: Sports Publishing, 2011.

Duren, Don. Boiling Out at the Springs: A History of Major League Baseball Spring Training at Hot Springs, Arkansas. Dallas, Texas: Hodge Printing Company, 2006.

Elmer Wright, accessed at www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/biographies.

Evansville Courier, January 24, 1937.

“FDR: Day by Day,” accessed at www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/daybyday.

Fimrite, Ron. “The Raging Rajah,” Sports Illustrated, October 2, 1995, accessed at http:// sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1007191/.

“Frosty Peters,” accessed at www.pro-football-reference.com/players/P/PeteFr21.htm.

Gay, Timothy M. Satch, Dizzy, and Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball before Jackie

Robinson. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Grand Forks Herald, August 29, 1901.

“Heartley ‘Hunk’ Anderson,” accessed at www.clkschools.org/hall_of_fame/Biographies. Heraldo de Brownsville, February 22, 1937.

Hervieux, Linda. “Bronx man remembers D-Day, visits cemetery in Normandy on anniversary of famed World War II invasion,” New York Daily News, June 5, 2009, accessed at http:// www.nydailynews.com/new-york/bronx/bronx-man-remembers-d-day-visits-cemetery- normandy-anniversary-famed-world-war-ii-invasion-article-1.373634.

“History of the Sheriffs of Scott County” accessed at www.co.scott.mn.us/countygov/aboutscott.

Hye, Allen E. “Fonseca, Lewis Albert ‘Lew,’” in Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball,

Volume 1, edited by David L. Porter. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000. Kalamazoo Gazette, January 23, 1921.

La Prensa (Los Angeles), February 22, 1936.

La Prensa (San Antonio), March 16, 1937.

Livingston, Ginger. “WWII Vet Shares Story with Students,” October 29, 2012, accessed at http://

blog.ecu.edu/sites/dailyclips/blog/2012/10/29/the-daily-reflector-4/. Miami Herald, April 30, 1913.

“My Day by Eleanor Roosevelt,” accessed at www.gwu.edu/~erpapers/myday. New Era, various issues, 1937.

New Orleans Item, September 20, 1901.

New Orleans Times Picayune, various issues, 1932-33; 1937.

Omaha World Herald, various issues, 1936-38; 1977.

Portland Oregonian, various issues, 1936-37.

Riverside Daily Press, various issues, 1937-38.

Rockford Morning Star, various issues, 1937.

Rockford Register-Republic, various issues, 1937-38.

Sargent, Jim. Ben Huffman, SABR Baseball Biography Project, accessed at http://sabr.org/bioproject. Sentinel-Record, various issues, 1937; 1960-61.

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The People’s Game. New York City, New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 1991.

Social Security Death Index, accessed at www.genealogybank.com/gbnk/ssdi/.

Sporting News, various issues, 1928; 1936-37; 1939-42; 1947-51; 1954-56; 1960-61.

Springfield Republican, various issues, 1937.

Waldo, Nancy. Telephone interview. June 20, 2013.

Wiest, Col. (Ret.) Albert. “Baseball As It Was: Before the War.” The 164th Infantry News, July 2012, 14- 16.

Posted in Untold Stories | Comments Off on Reaching for the Brass Ring: A Portrait of Doan’s 1937 Baseball School

Baseball purists know this time of year means more than just transi- tioning from winter to spring. Spring training camps in sunny Florida and Arizona are now in full swing for all 30 Major League Baseball teams.

Baseball purists know this time of year means more than just transi- tioning from winter to spring. Spring training camps in sunny Florida and Arizona are now in full swing for all 30 Major League Baseball teams. The White Stockings practiced and played there that first year. A giant oak tree on the courthouse lawn dates back to that time. The White Stockings won the pennant that year, and more teams joined them in finding spots in the south to train for the season. “By 1915, all of the big league teams in baseball had trained in Hot Springs at some point,” Dugan said. Other teams that quickly followed the White Stockings to Hot Springs included the Pittsburgh Pirates, Cleveland Spiders and Cincinnati Reds, plus a host of minor league clubs. The Spiders featured, arguably, the great- est pitcher of all time, Cy Young. “Cy Young also played for the Red Sox and loved Hot Springs so much he returned regularly after he retired,” Dugan said. Young, baseball’s all-time winningest pitcher with 511 career victories, announced his retirement from the game in Hot Springs before the season started in 1911, changed his mind, then quit at the end of the sea- son. In 1938, the city celebrated Cy Young Day and honored him with a parade down- town. Chicago sold its field on Ouachita Ave. in 1896. Soon, other fields sprang up at the end of the trolley lines on Whittington Avenue.

The White Stockings practiced and played there that first year. A giant oak tree on the courthouse lawn dates back to that time. The White Stockings won the pennant that year, and more teams joined them in finding spots in the south to train for the season. “By 1915, all of the big league teams in baseball had trained in Hot Springs at some point,” Dugan said. Other teams that quickly followed the White Stockings to Hot Springs included the Pittsburgh Pirates, Cleveland Spiders and Cincinnati Reds, plus a host of minor league clubs. The Spiders featured, arguably, the great- est pitcher of all time, Cy Young. “Cy Young also played for the Red Sox and loved Hot Springs so much he returned regularly after he retired,” Dugan said. Young, baseball’s all-time winningest pitcher with 511 career victories, announced his retirement from the game in Hot Springs before the season started in 1911, changed his mind, then quit at the end of the sea- son. In 1938, the city celebrated Cy Young Day and honored him with a parade down- town. Chicago sold its field on Ouachita Ave. in 1896. Soon, other fields sprang up at the end of the trolley lines on Whittington Avenue. It became Fogel Field, named for Horace Fogel, owner of the Phillies. The baseball diamond is gone, but the field is still there. Other big league teams that later trained in Hot Springs included the St. Louis Cardinals and Philadelphia Athletics. Unlike players today who sign auto- graphs at the ballpark but seldom mingle publicly with fans, the early stars often lounged in hotel lobbies or walked along Central Avenue and bathhouse row posing for photos with fans. “They were accessible to the public,” said Steve Arrison, chief executive officer of the Hot Springs Advertising and Promotion Commission. “Though some, like Ruth, were larger than life, they enjoyed their celebrity status and didn’t shy away from their fans.” Arrison says it was a historic time in the city’s past when movie stars, entertain- ers and celebrities regularly visited Hot Springs. According to Dugan, Arrison and other historians of that period, the national pastime ruled the city from late February through March.

It became Fogel Field, named for Horace Fogel, owner of the Phillies. The baseball diamond is gone, but the field is still there. Other big league teams that later trained in Hot Springs included the St. Louis Cardinals and Philadelphia Athletics. Unlike players today who sign auto- graphs at the ballpark but seldom mingle publicly with fans, the early stars often lounged in hotel lobbies or walked along Central Avenue and bathhouse row posing for photos with fans. “They were accessible to the public,” said Steve Arrison, chief executive officer of the Hot Springs Advertising and Promotion Commission. “Though some, like Ruth, were larger than life, they enjoyed their celebrity status and didn’t shy away from their fans.” Arrison says it was a historic time in the city’s past when movie stars, entertain- ers and celebrities regularly visited Hot Springs. According to Dugan, Arrison and other historians of that period, the national pastime ruled the city from late February through March.